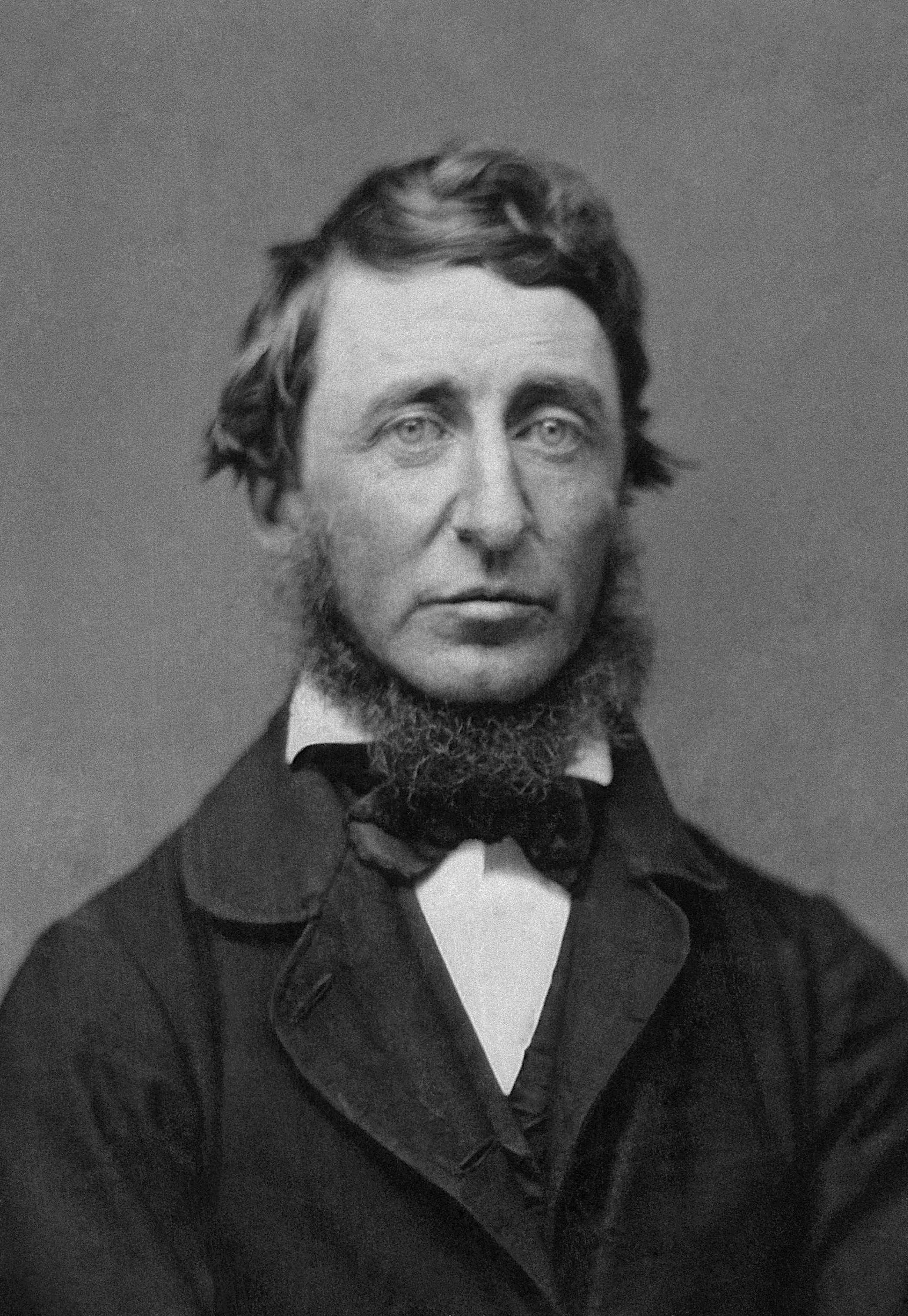

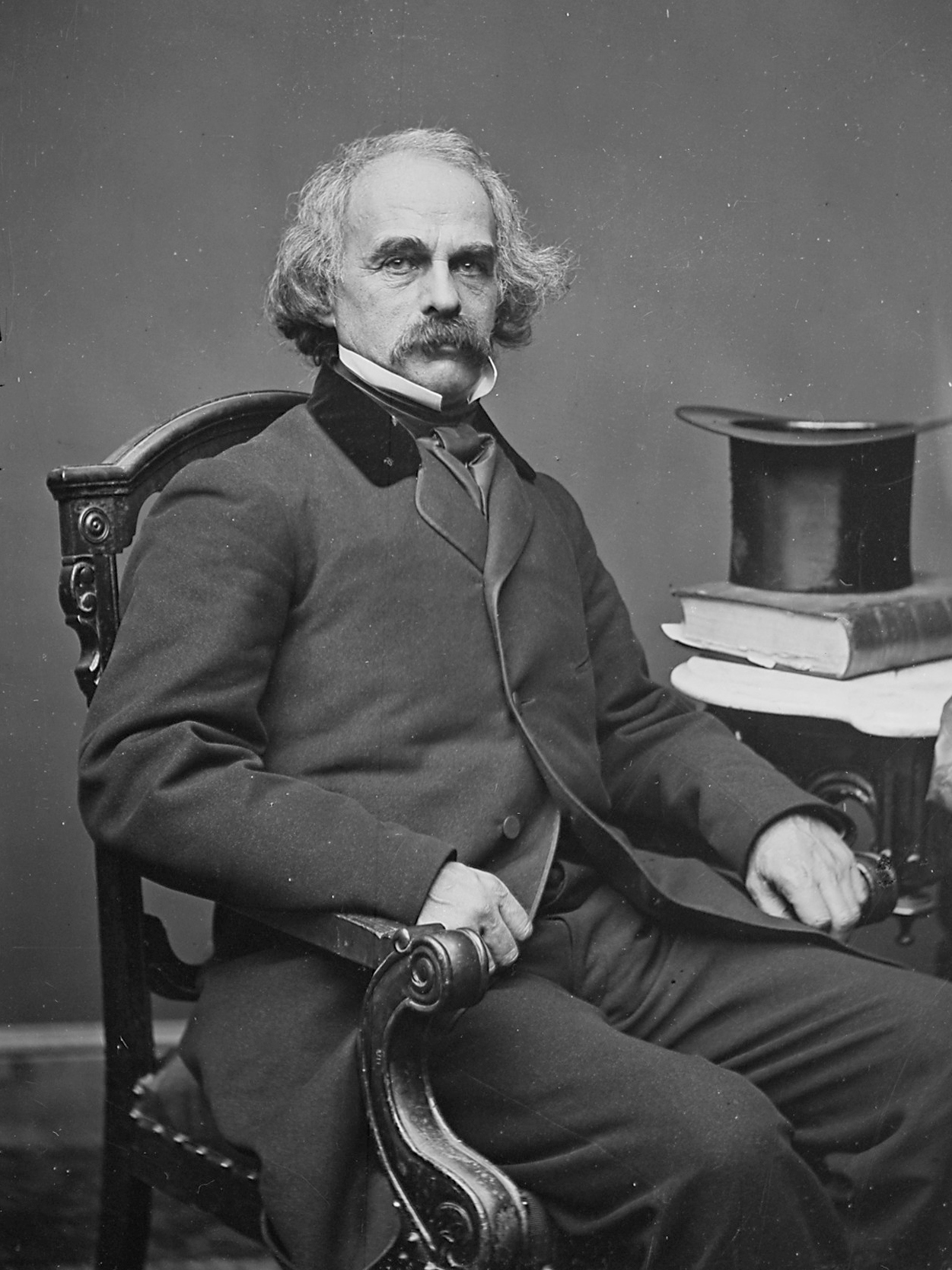

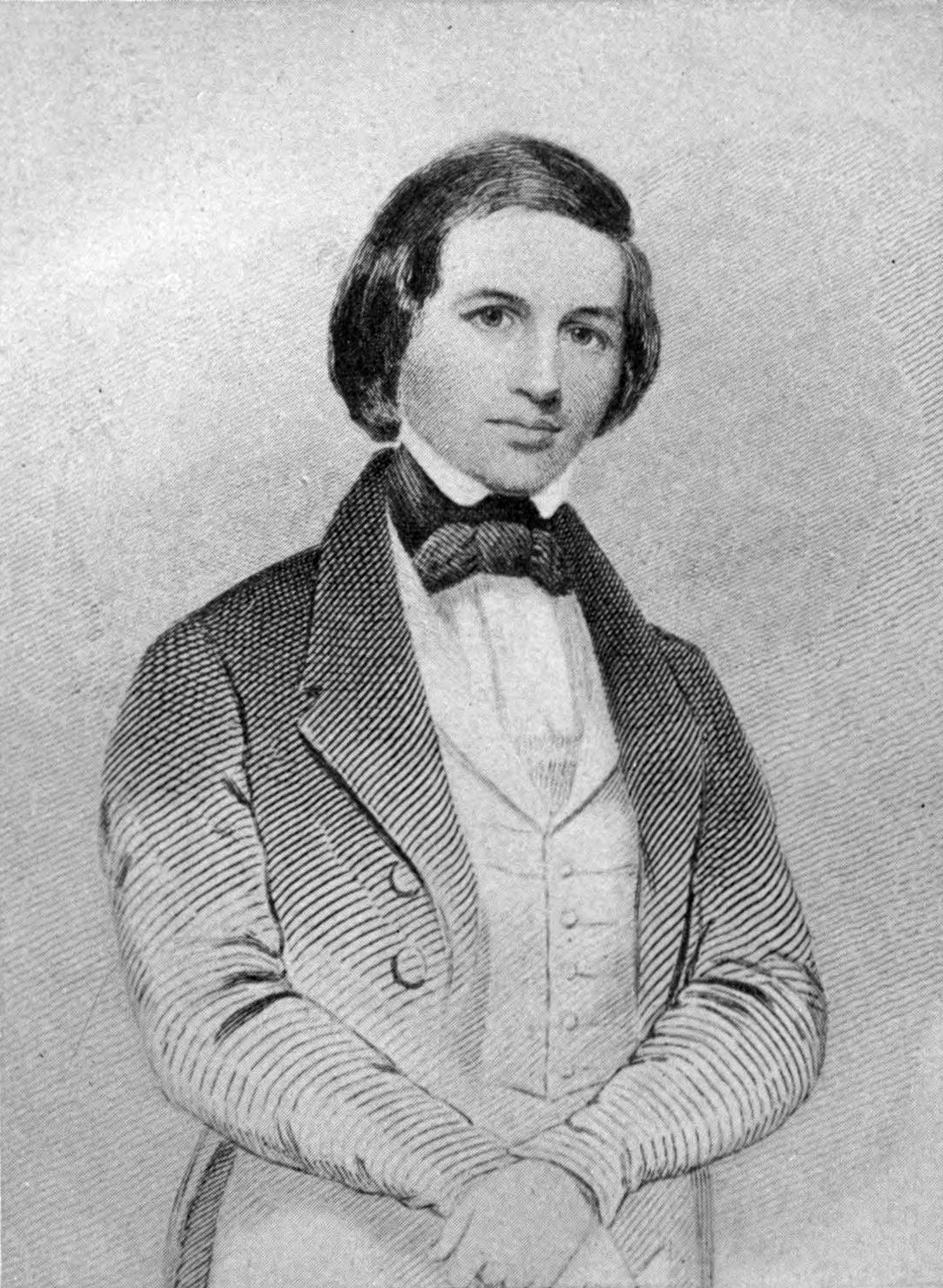

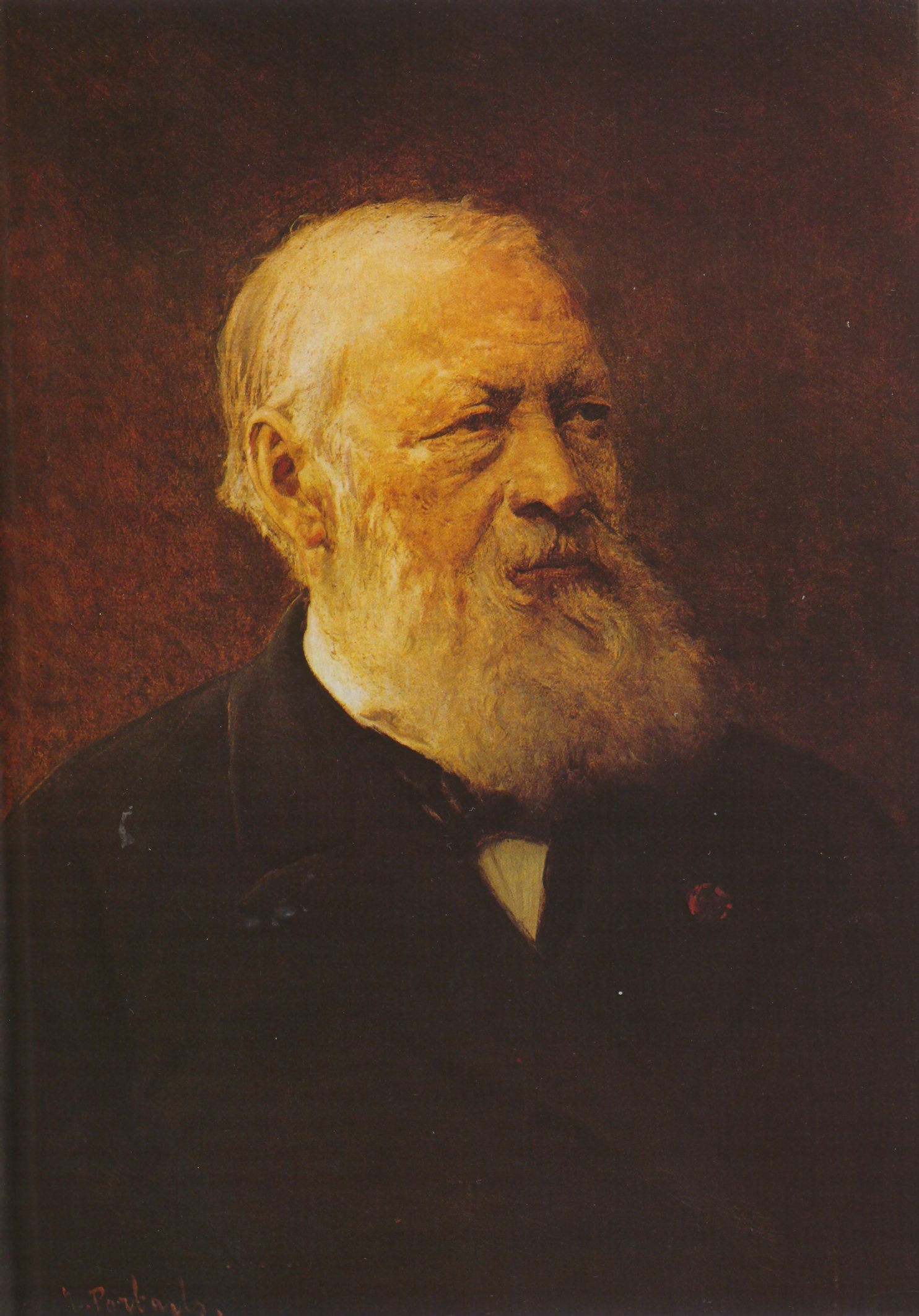

Nathaniel Parker Willis

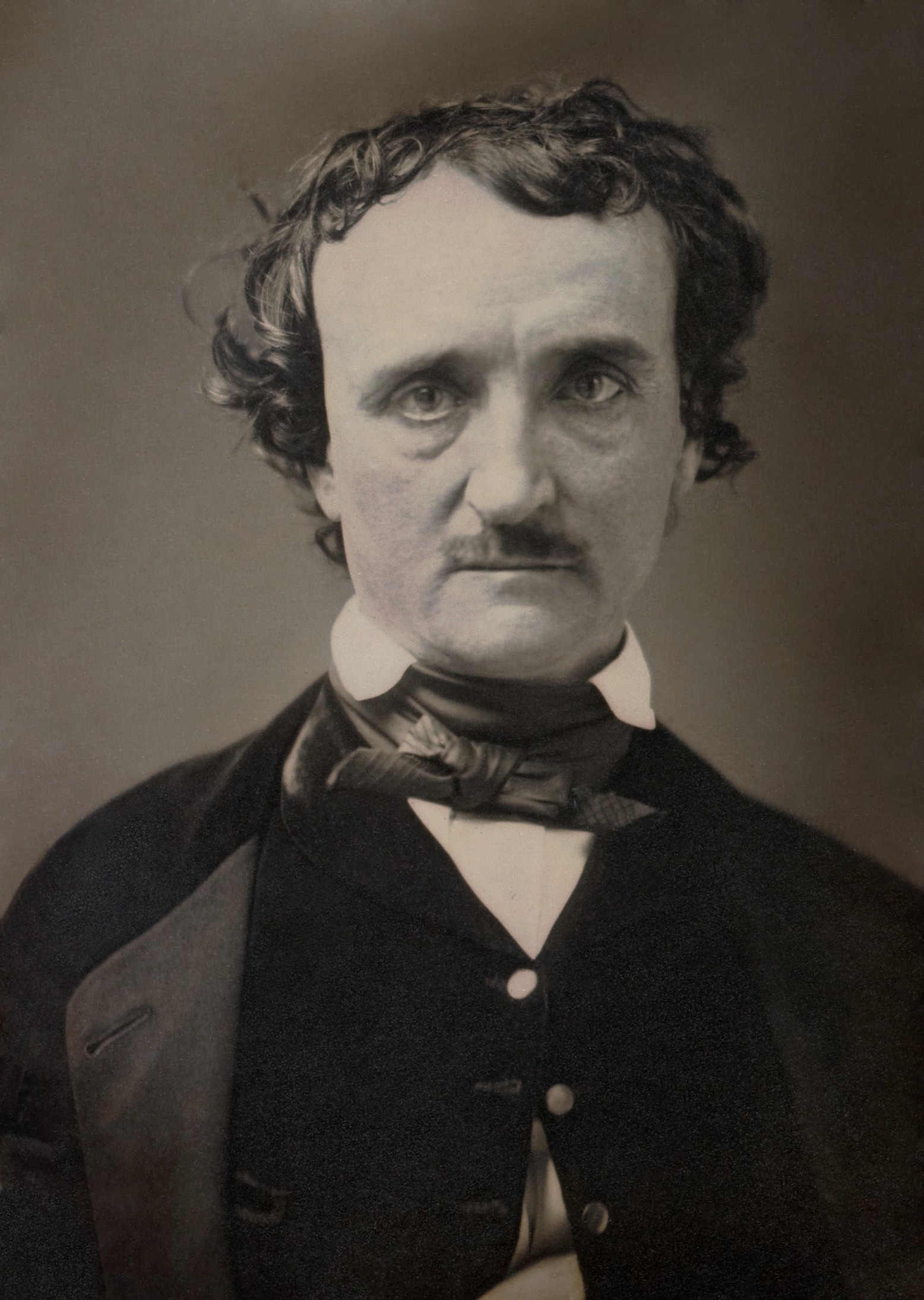

Nathaniel Parker Willis was an influential American writer, poet, and editor, known for his significant contributions to 19th-century American literature. Born in Portland, Maine, he hailed from a family deeply rooted in publishing, which fostered his early interest in literature. After graduating from Yale College, Willis began his career as an overseas correspondent for the New York Mirror, quickly establishing himself as a prominent literary figure in New York City. He became the highest-paid magazine writer of his time, earning substantial sums for his articles and gaining a reputation for his engaging travel writings that often included personal addresses to his readers. In 1846, he founded the Home Journal, later renamed Town & Country, further solidifying his influence in the literary world. Willis's body of work included poetry, tales, and a play, and he collaborated with notable contemporaries such as Edgar Allan Poe and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. His writing style was characterized by a blend of personal reflection and social commentary, which resonated with a wide audience during his lifetime. However, despite his initial popularity and the esteem in which he was held, Willis's legacy faded after his death in 1867, leaving him largely forgotten in the annals of American literature. His work, while celebrated in his era, has been critiqued for its perceived effeminacy and European influences, as noted by contemporaries, including his sister, Fanny Fern. Today, Willis's contributions are recognized as part of the broader tapestry of American literary history, reflecting the complexities of his time and the evolution of literary forms.

Famous Quotes

View all 3 quotes“There they stand, the innumerable stars, shining in order like a living hymn, written in light.”

“Nature has wrought with a bolder hand in America.”

“The hidden beauties of standard authors break upon the mind by surprise. It is like discovering a secret spring in an old jewel. You take up the book in an idle moment, as you have done a thousand times before, perhaps wondering, as you turn over the leaves, what the world finds in it to admire, when suddenly, as you read, your fingers press close upon the covers, your frame thrills, and the passage you have chanced upon chains you like a spell,—it is so vividly true and beautiful. Milton’s ‘Comus’ flashed upon me in this way. I never could read the ‘Rape of the Lock’ till a friend quoted some passages from it during a walk. I know no more exquisite sensation than this warming of the heart to an old author; and it seems to me that the most delicious portion of intellectual existence is the brief period in which, one by one, the great minds of old are admitted with all their time-mellowed worth to the affections.”