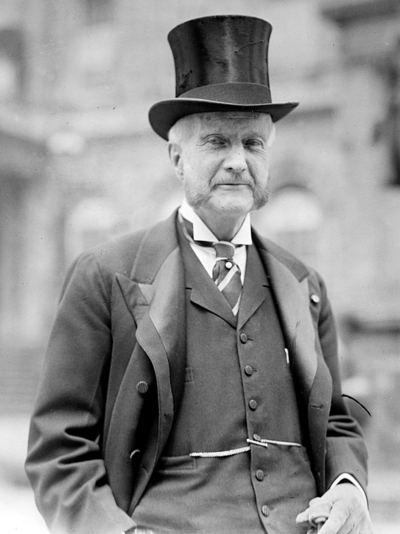

David Ames Wells

David Ames Wells was an influential American engineer, economist, and author, known for his advocacy of low tariffs and his contributions to scientific education. Born in Springfield, Massachusetts, he graduated from Williams College in 1847 and later studied at the Lawrence Scientific School, where he worked alongside the renowned naturalist Louis Agassiz. His early career included editing 'The Annual of Scientific Discovery' and inventing devices for textile mills, showcasing his innovative spirit. Wells authored several important textbooks, including 'The Science of Common Things' and 'Wells's Principles and Applications of Chemistry,' which became widely used in educational institutions. Wells gained prominence as a political economist during the Civil War, particularly through his address 'Our Burden and Our Strength,' which highlighted the United States' capacity to manage its national debt. This work caught the attention of President Abraham Lincoln, leading to Wells's appointment as chairman of the National Revenue Commission in 1865. In this role, he was instrumental in collecting economic data for government use, and his recommendations helped shape fiscal policy in the post-war era. His legacy lies in his contributions to both scientific education and economic policy, marking him as a significant figure in 19th-century American thought.

Famous Quotes

View all 2 quotes“... it will appear that there is no such thing as fixed capital; there is nothing useful that is very old except the precious metals, and all life consists in the conversion of forms. The only capital which is of permanent value is immaterial--the experience of generations and the development of science.”

“Previous to 1872, nearly all the calicoes of the world were dyed or printed with a coloring principle extracted from the root known as "madder"; the cultivation and preparation of which involved the use of thousands of acres of land in Holland, Belgium, Eastern France, Italy, and the Levant, and the employment of many hundreds of men, women, and children, and of large amounts of capital; the importation of madder into England for the year 1872 having been 28,731,600 pounds, and into the United States for the same year 7,780,000 pounds. To-day, two or three chemical establishments in Germany and England, employing but few men and a comparatively small capital, manufacture from coal-tar, at a greatly reduced price, the same coloring principle; and the former great business of growing and preparing madder with the land, labor, and capital involved is gradually becoming extinct; the importations into Great Britain for the year 1885 having declined to 2,472,000 pounds, and into the United States to 1,458,313 pounds.”