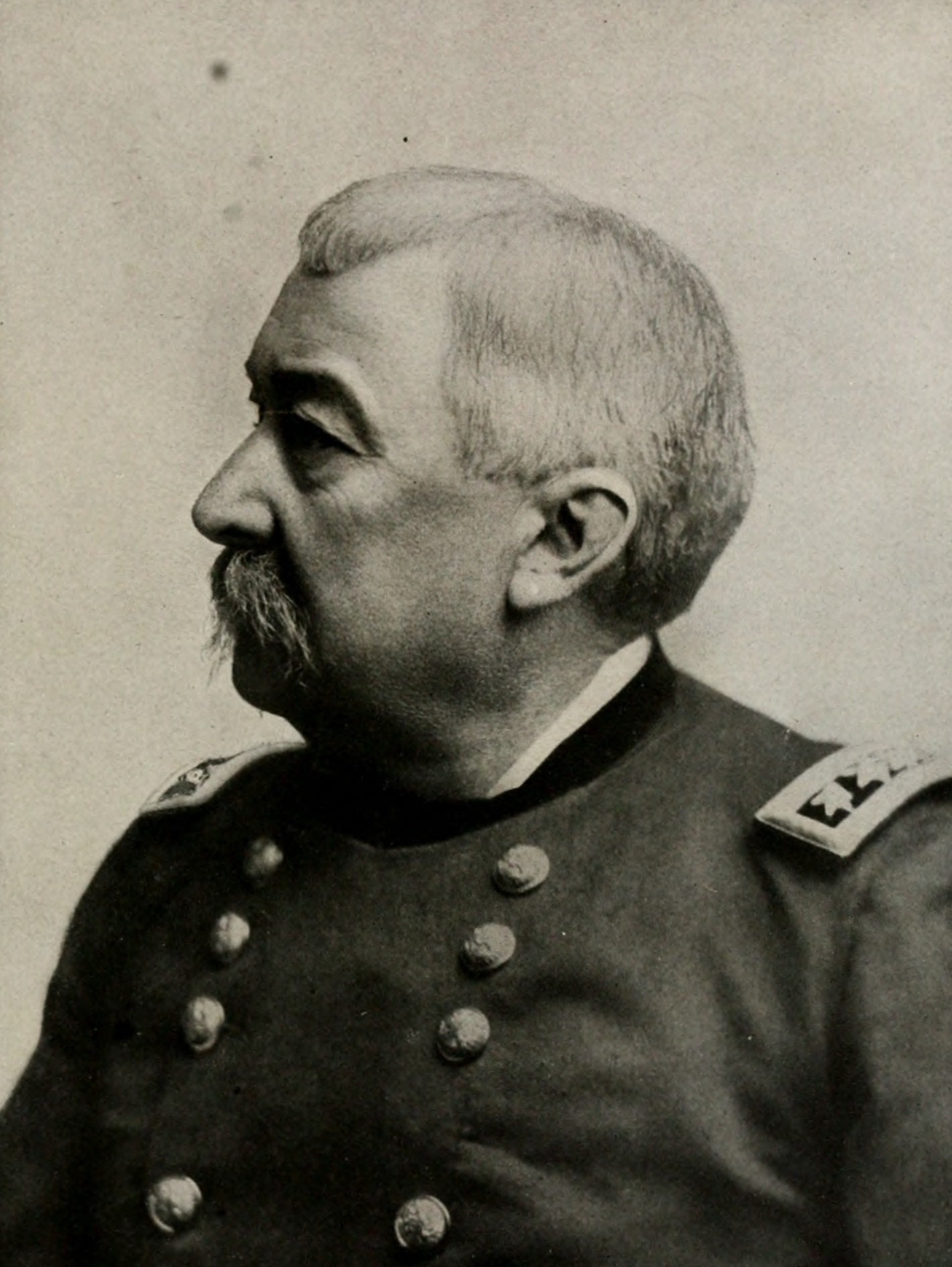

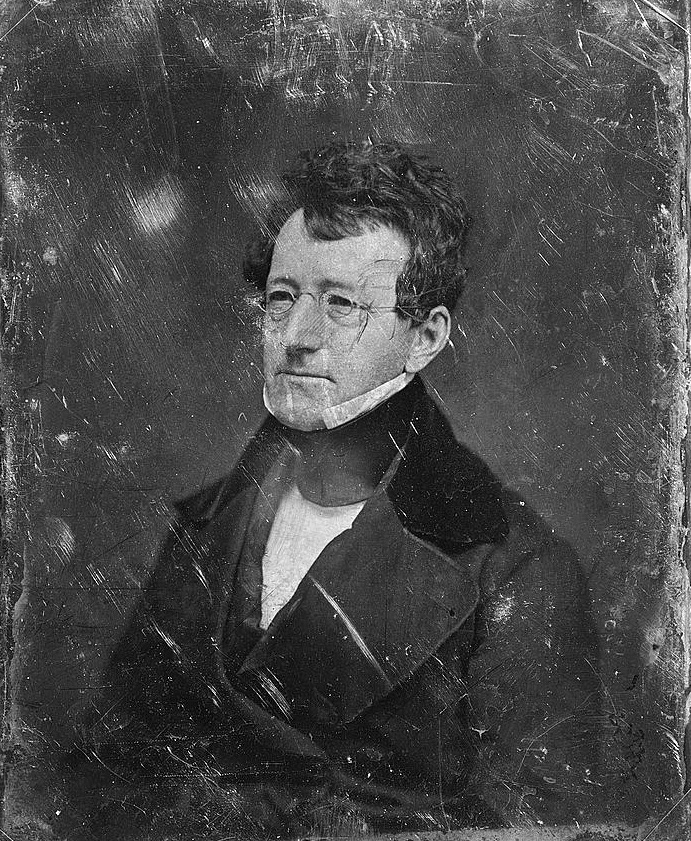

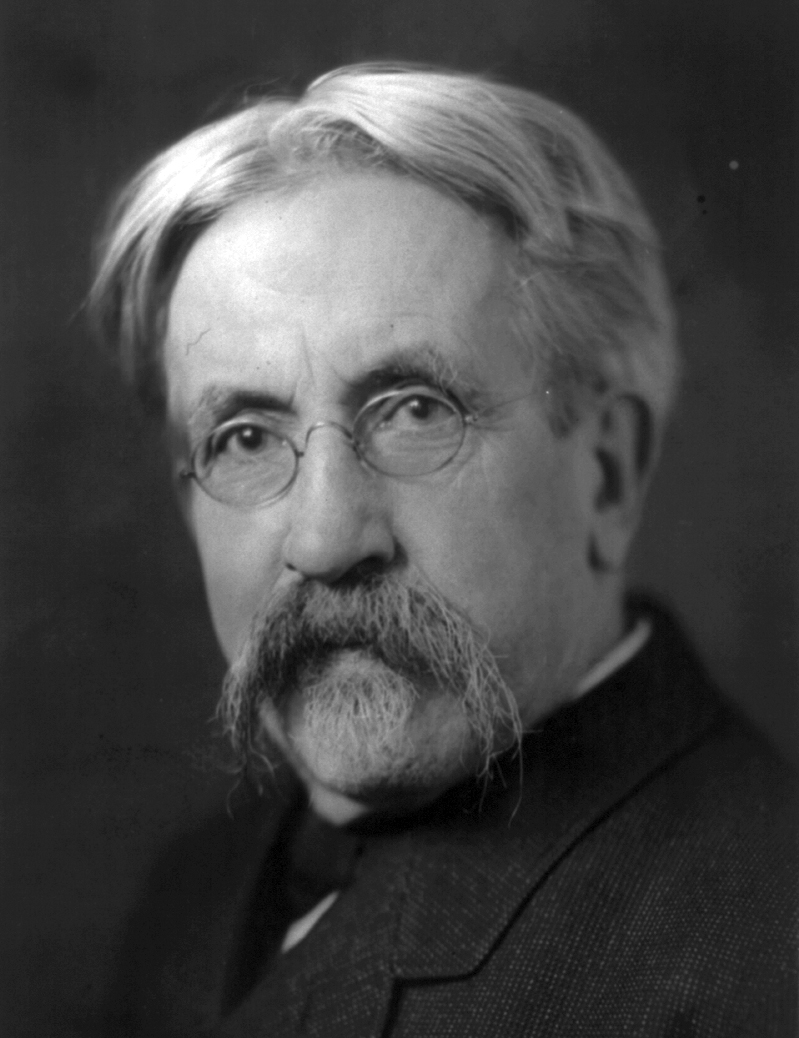

Henry Clews

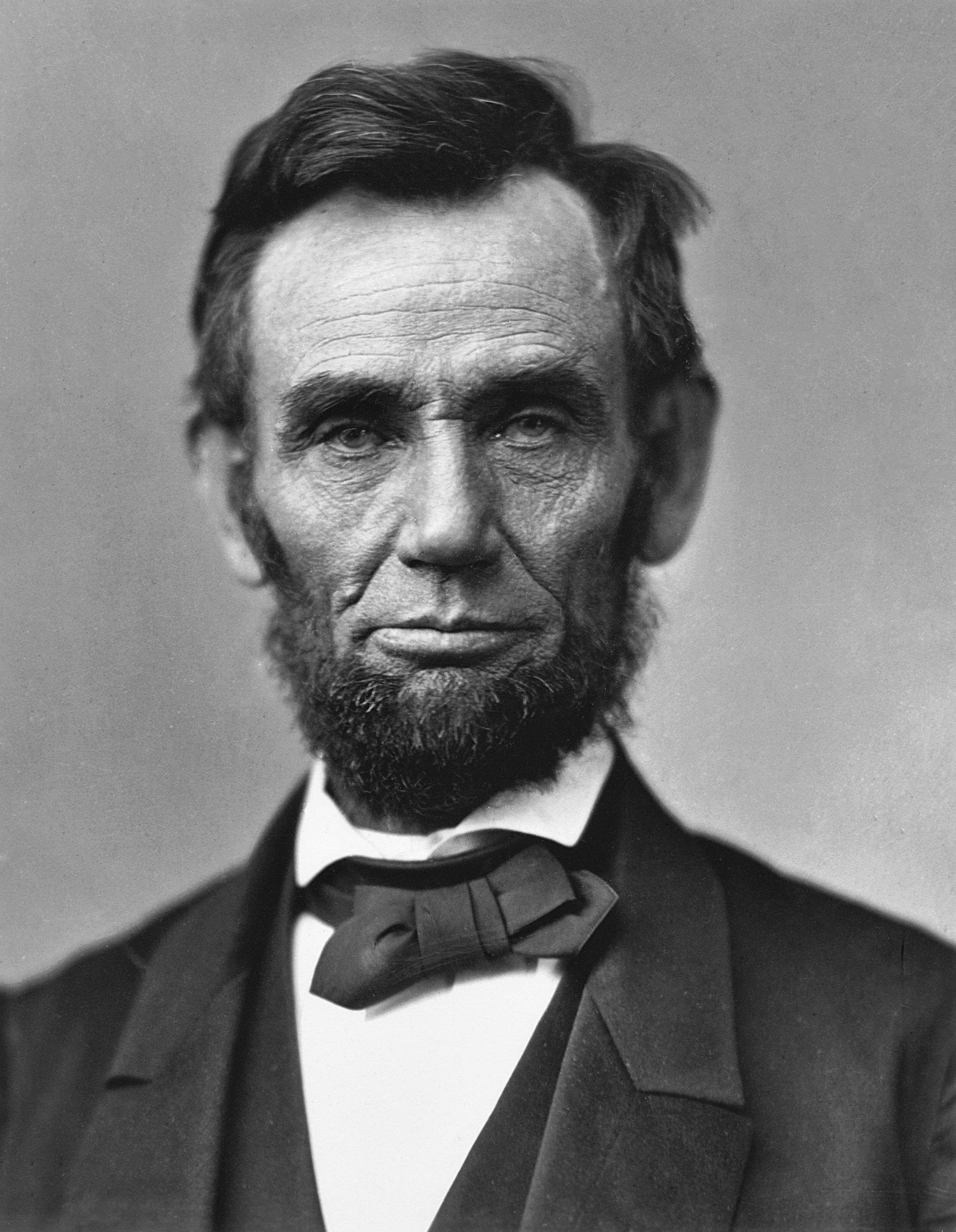

Henry Clews was a British-American financier and author known for his significant contributions to the financial landscape of the United States in the 19th century. Born in Staffordshire, England, he emigrated to the United States around 1850, where he co-founded an investment company that became the second-largest marketer of federal bonds during the American Civil War. His financial acumen earned him a position as an economic advisor to President Ulysses S. Grant, and he maintained a friendship with President Abraham Lincoln, further intertwining his life with pivotal moments in American history. In addition to his financial pursuits, Clews was an active participant in New York City politics, notably organizing the "Committee of 70," which played a crucial role in dismantling the corrupt Tweed Ring. His literary contributions include the influential book "Fifty Years in Wall Street," published in 1887, where he shared insights from his extensive experience in the financial sector. Clews held conservative economic views and was critical of the labor union movement, reflecting the complexities of his time and his perspectives on economic reform and governance. His legacy endures through his writings and his impact on both finance and politics in America.

Famous Quotes

View all 3 quotes“But few gain sufficient experience in Wall Street to command sucess until they reach that period of life in which they have one foot in the grave. When this time comes these old veterans of the Street usually spend long intervals of repose at their comfortable homes, and in times of panic, which recur sometimes oftener than once a year, these old fellows will be seen in Wall Street, hobbling down on their canes to their brokers' office. Then they always buy good stocks to the extent of their bank balances, which have been permitted to accumulate for just such an emergency. The panic usually rages until enough of these cash purchases of stock is made to afford a big "rake in." When the panic has spent its force, these old fellows, who have been resting judiciously on their oars in expectation of the inevitable event, which usually returns with the regularity of the seasons, quickly realize, deposit their profits with their bankers, or the overplus thereof, after purchasing more real estate that is on the upgrade, for permanent investment, and retire for another season to the quietude of their splendid homes and the bosoms of their happy families. If young men had only the patience to watch the speculative signs of the times, as manifested in the periodical egress of these old prophetic speculators from their shells of security, they would make more money at these intervals than by following up the slippery "tips" of the professional "pointers" of the Stock Exchange all the year round, and they would feel no necessity for hanging at the coat tails, around the hotels, of those specious frauds, who pretend to be deep in the councils of the big operations and of all the new "pools" in process of formation. I say to the young speculators, therefore, watch the ominous visits to the Street of these old men. They are as certain to be seen on the eve of a panic as spiders creeping stealthily and noiselessly from their cobwebs just before rain.”

“The action of commerce, like the motion of the sea or the atmosphere, follows an undulatory line. First comes an ascending wave of activity and rising prices; next, when prices have risen to a point that checks demand, comes a period of hesitation and caution; then, care among lenders and discounters; then comes the descending movement, in which holders simultaneously endeavor to realize, thereby accelerating a general fall in prices. Credit then becomes more sensitive and is contracted; transactions are diminished; losses are incurred through the depreciation of property, and finally the ordeal becomes so severe to the debtor class that forcible liquidation has to be adopted, and insolvent firms and institutions must be wound up. This process is a periodical experience in every country; and the extent of the destructiveness of the crisis that attends it depends chiefly on the steadiness and conservatism of the business methods in each particular community affected.”

“No man of average common sense would trust a case in law to a bar room "bummer" who would assert that he was well acquainted with Aaron J. Vanderpoel, Roscoe Conkling, and Win. M. Evarts, and had got all the inside "tips" from these legal lights on the law relating to the case in question. The fellow would be laughed at, and, in all probability, if he persisted in this kind of talk, would be handed over to the city physician to be examined in relation to his sanity, but in Wall Street affairs men can every day make similar pretensions and pass for embodiments of speculative wisdom.”