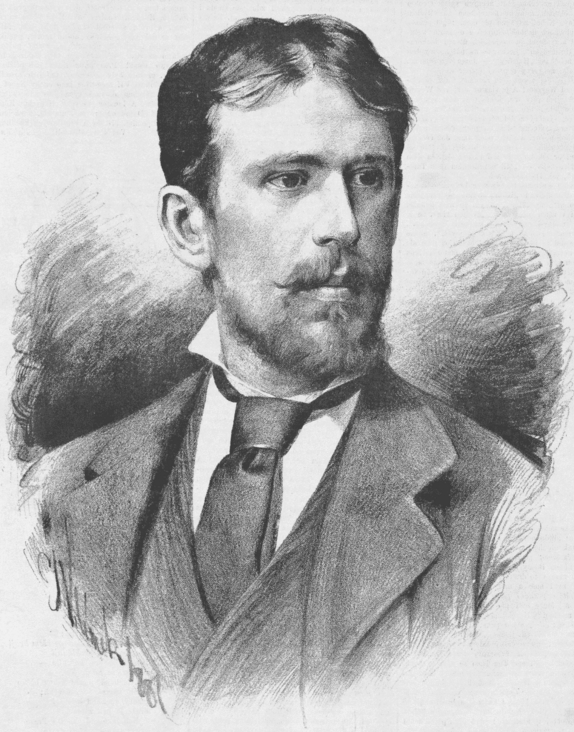

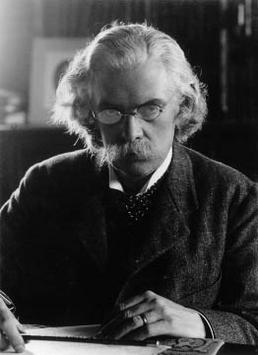

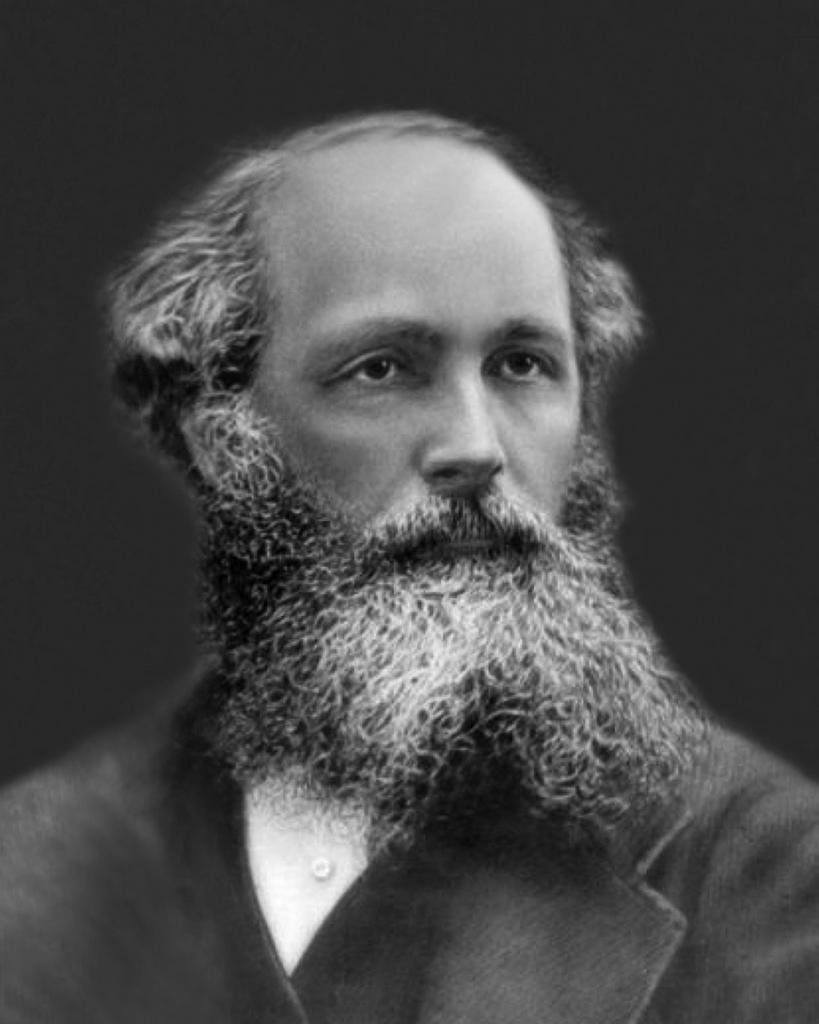

Felix Klein

Felix Klein was a prominent German mathematician and educator whose contributions significantly shaped modern mathematics. He is best known for his 1872 Erlangen program, which provided a groundbreaking classification of geometries based on their symmetry groups, establishing a foundational framework that influenced the study of geometry and group theory. Klein's work spanned various areas, including complex analysis and non-Euclidean geometry, and he was instrumental in linking these fields through his innovative ideas. During his tenure at the University of Göttingen, Klein transformed the institution into a leading center for mathematical research by introducing new lectures, professorships, and institutes. His commitment to mathematics education reform was evident as he advocated for improved teaching methods at all educational levels. In 1908, he became the first president of the International Commission on Mathematical Instruction, further solidifying his legacy as a champion of mathematics education both in Germany and internationally. Klein's influence extended beyond his own research, as he played a crucial role in fostering a collaborative environment for mathematicians, leaving an enduring impact on the field of mathematics and its pedagogy.

Famous Quotes

View all 3 quotes“Undoubtedly, the capstone of every mathematical theory is a convincing proof of all of its assertions. Undoubtedly, rnathematics inculpates itself when it foregoes convincing proofs. But the mystery of brilliant productivity will always be the posing of new questions, the anticipation of new theorems that make accessible valuable results and connections. Without the creation of new viewpoints, without the statement of new aims, mathematics would soou exhaust itself in the rigor of its logical proofs and begin to stagnate as its substance vanishes. Thus, in a sense, mathematics has been most advanced by those who distinguished thernselves by intuition ratber than by rigorous proofs.”

“Regarding the fundamental investigations of mathematics, there is no final ending ... no first beginning.”

“In mathematics, however, as everywhere else, men are inclined to form parties, so that there arose schools of pure synthesists and schools of pure analysts, who placed chief emphasis upon absolute “purity of method,” and who were thus more one-sided than the nature of the subject demanded. Thus the analytic geometricians often lost themselves in blind calculations, devoid of any geometric representation, The synthesists, on the other hand, saw salvation in an artificial avoidance of all formulas, and thus they accomplished nothing more, finally, than to develop their own peculiar language formulas, different from ordinary formulas.”