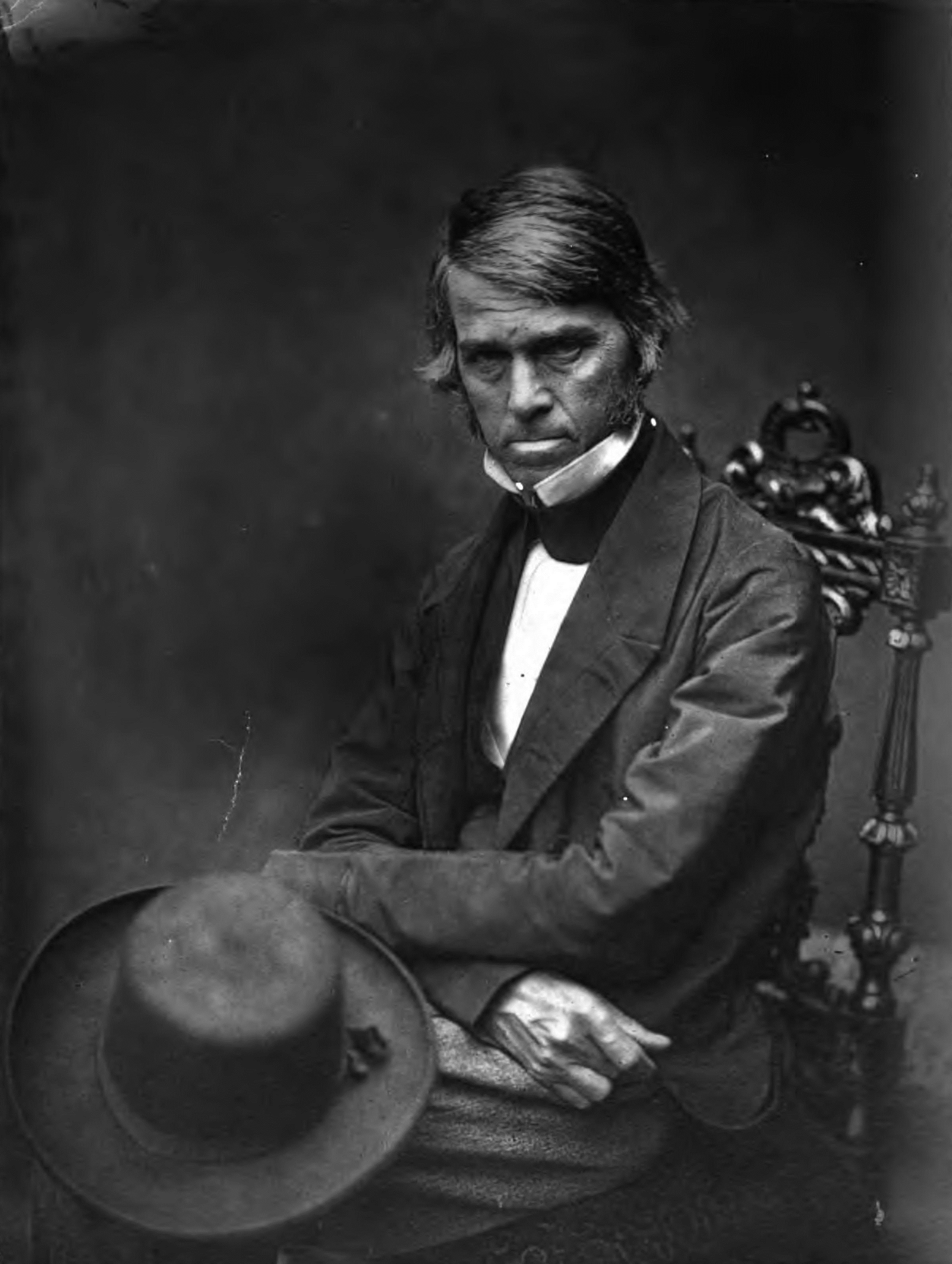

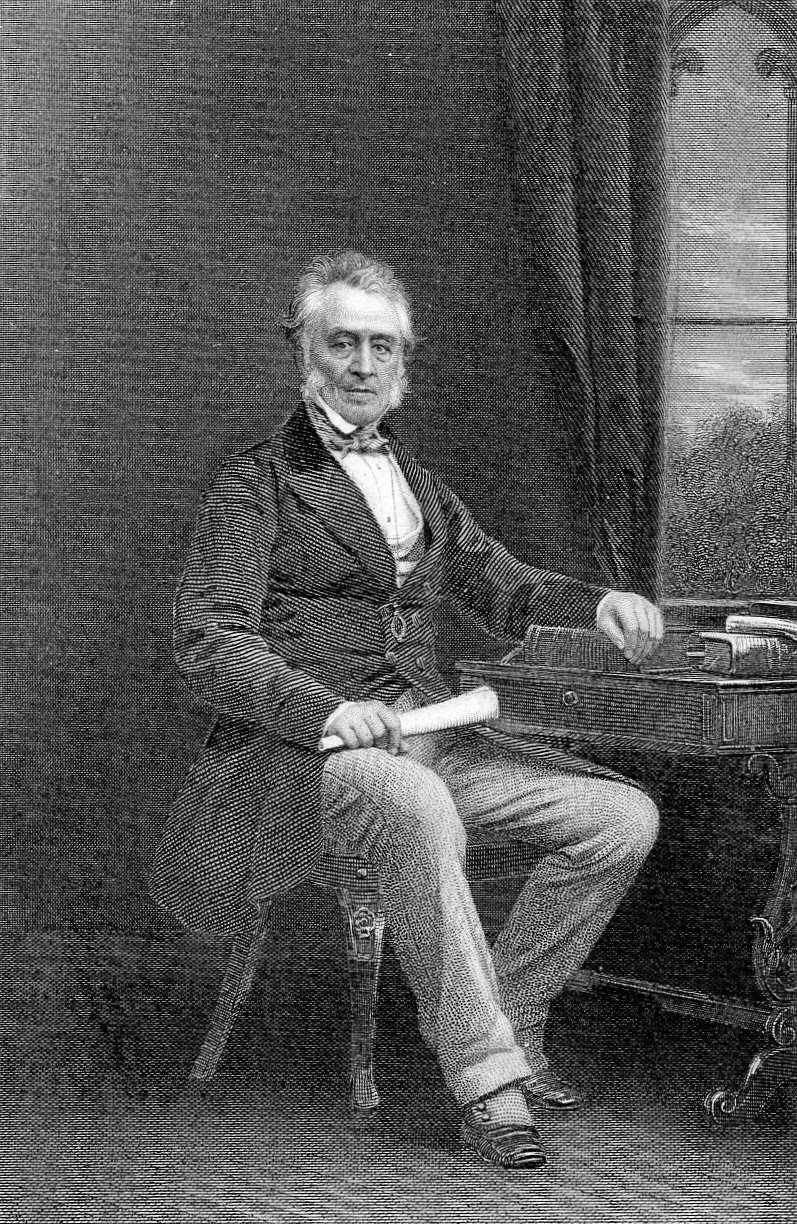

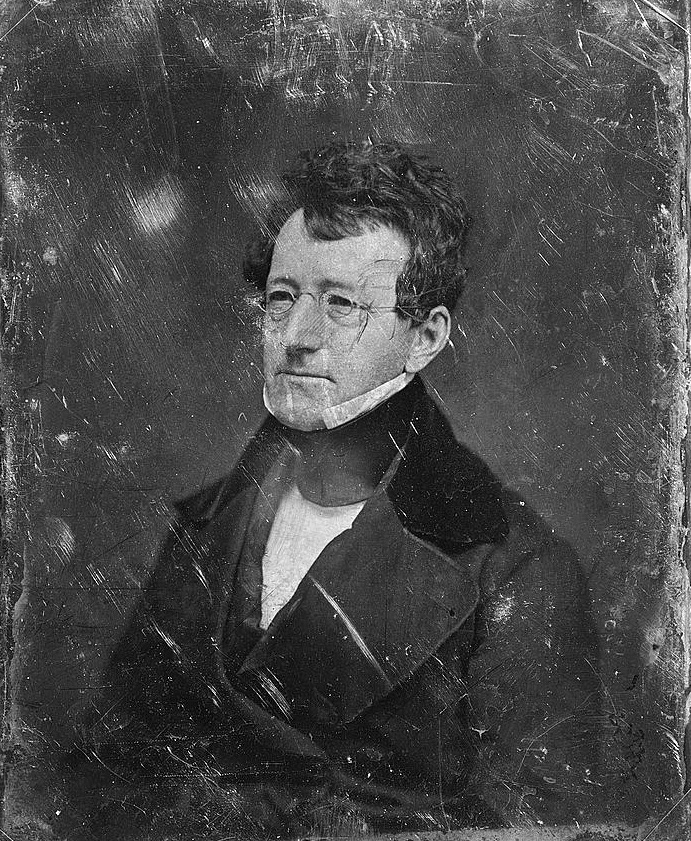

William Hickling Prescott

William Hickling Prescott was an influential American historian and Hispanist, recognized as the first American scientific historian. Despite facing significant visual impairment, which often hindered his ability to read and write independently, Prescott's remarkable eidetic memory allowed him to produce some of the most important historical works of the 19th century. His extensive studies focused on late Renaissance Spain and the early Spanish Empire, culminating in seminal texts such as The History of the Reign of Ferdinand and Isabella the Catholic (1837), The History of the Conquest of Mexico (1843), and A History of the Conquest of Peru (1847). His unfinished work, History of the Reign of Philip II, further solidified his reputation as a leading intellectual of his time. Prescott's contributions to historiography were significant, as he emphasized a narrative style that combined meticulous research with engaging prose. His approach to history was characterized by a systematic use of archives and a focus on political and military events, often at the expense of economic and social contexts. This method not only made his works accessible to a broader audience but also established a model for future historians. Prescott's legacy endures through his impact on the study of both Spain and Mesoamerica, and he remains one of the most widely translated American historians, celebrated for his role in elevating history to a rigorous academic discipline.

Famous Quotes

View all 3 quotes“a government, which does not rest on the sympathies of its subjects, cannot long abide; that human institutions, when not connected with human prosperity and progress, must fall, if not before the increasing light of civilisation, by the hand of violence; by violence from within, if not from without. And who shall lament their fall?”

“The life of the Spanish discoverers was one long day-dream. Illusion after illusion chased one another like the bubbles which the child throws off from his pipe, as bright, as beautiful, and as empty. They lived in a world of enchantment.”

“But, to judge the action fairly, we must transport ourselves to the age when it happened.”